If the GPU contributes significant heat, then that will cause the CPU to throttle more aggressively. Premiere uses both the CPU and the GPU, while Geekbench only uses the CPU. So what’s going on here? Why does this test not replicate the throttling seen in other tests? Part of the issue is the test themselves.

#Intel power gadget 2018 pro#

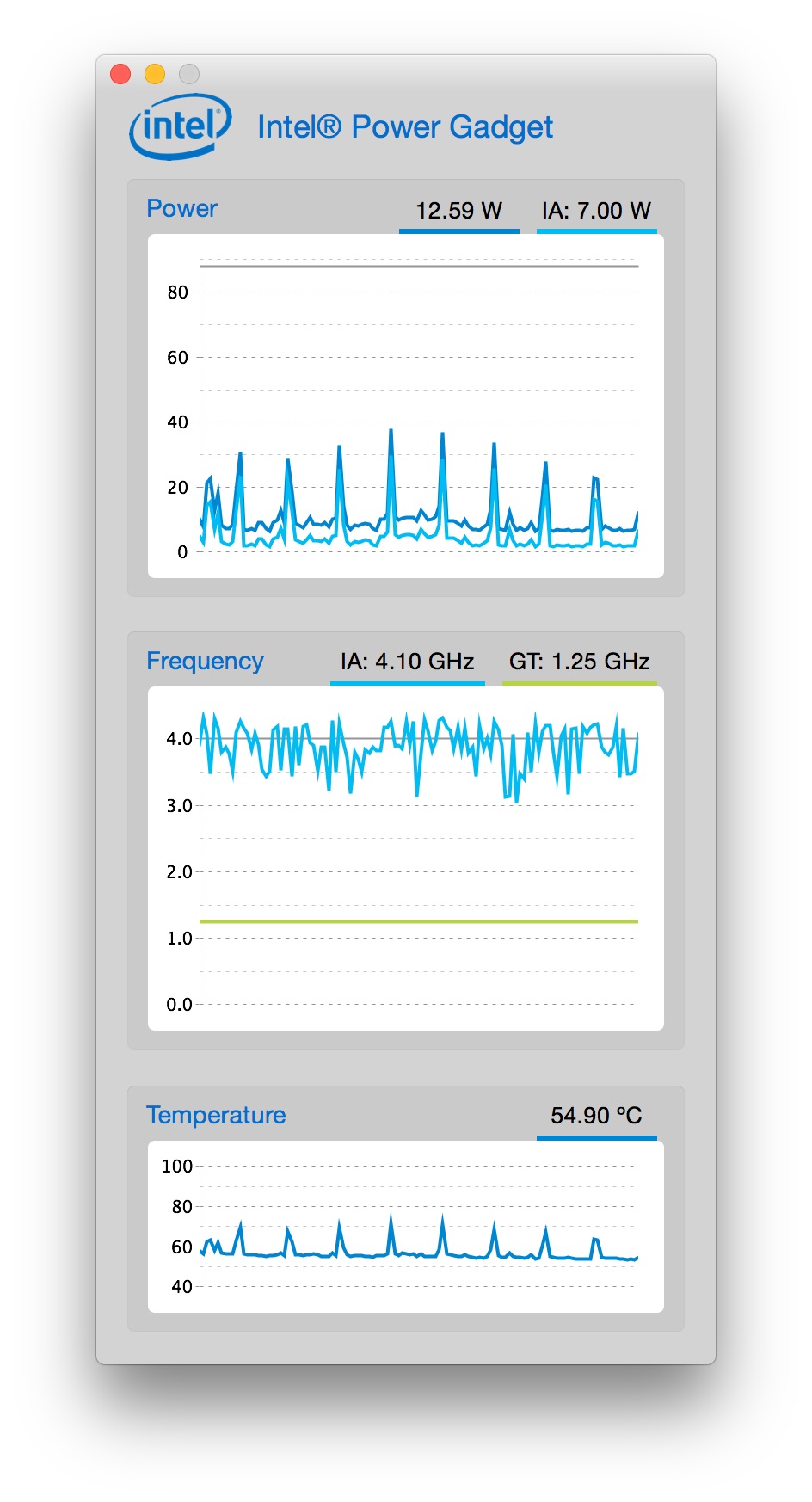

When running the stress test I also ran the Intel Power Gadget on the MacBook Pro (Mid 2018):Įven under sustained load, the i7 processor was running at 3.0-3.1 GHz, well above the processor’s base frequency of 2.6 GHz. If you compare the multi-core scores with the build times, you’ll see that a higher multi-core score predicts a lower build time. Let’s also take a look at the multi-core Geekbench 4 scores for these Macs:

The low variations suggest no significant throttling is happening in any of the Macs. The laptop Macs have a higher, but still reasonable, run-to-run variation of 2.6% and 3.9%.

#Intel power gadget 2018 mac#

The desktop Macs have a very low run-to-run variation, with the Coefficient of Variation (CoV) less than 0.5% for the Mac Pros and the iMac. Let’s take a look at the build time variation for the Macs: Model The 4-core MacBook Pro is significantly slower than the 6-core MacBook Pro, taking 46% longer to build Geekbench. However, the 6-core MacBook Pro is a close second, taking 25% longer to build Geekbench. Unsurprisingly the 12-core Mac Pro is the fastest Mac. Here are the median build times for the Macs: While I don’t have access to an i9 model yet, I expect the i7 to throttle similarly to the i9 when running multi-core tasks. I ran the stress test on several Macs in the Primate Labs office, including a MacBook Pro (Mid 2018) with an i7 processor. The stress test takes between 30 minutes and 60 minutes to complete. Each iteration is timed separately to see if performance changes over time. The stress test emulates a developer workload by building Geekbench 4 from scratch ten times in a row. To test whether this is the case, I wrote a quick stress test. What happens when after a year or so dust starts to build up inside the case? Performance is likely to suffer more and more over time, since the ability of the MacBook Pro to cool itself will decrease with time as a fine layer of dust builds up in the sealed clamshell design.There is increasing concern that the new 6-core MacBook Pros (in particular the i9 model) throttle under sustained load to the point where they are slower than the old 4-core MacBook Pros. Since the decline is less than 10%, this performance is a major improvement over previous models in terms of sustained consistent performance.Ĭreating an air gap under the MacBook Pro and then using a fan to blow air under it did not result in any difference in behavior at an ambient temperature of about 75☏. This is a far better result than the 28% decline seen with the 2017 MacBook Pro. 3 seconds, but within 11 iterations it declines to ~7.1 seconds and (on average) stays that way, never again going as fast as initially. Degraded performance with sustained usageīelow are times for iterations of the Photoshop sharpening test, repeated 500 times.Īt first the time is in the range of ~6. The question addressed here is whether and by how much the 2018 MacBook Pro declines in performance as compared to the 2017 MacBook Pro. This little secret is not mention in the “brag sheet” aka specifications-not so nice. Disabling the GPU resulted in identical performance when tasks use the CPU instead. Investigation with the 2017 MacBook Pro determined that turns out that this is a GPU throttling behavior. No such pattern was seen on the iMac 5K or 2013 Mac Pro. For example, with repeated iterations of of the Photoshop sharpening test, the 2017 MacBook Pro was seen to decline in performance by up to 28% after as little as 30 seconds. While testing the 20 (and 2016) MacBook Pro, a pattern was noticed in that performance declines with each iteration of some tests.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)